sustainability & habitation

Space is very important to us. It encompasses our personal possessions and our psychological state of mind. Most of the world's human population inhabit some sort of urbanized area and this number continues to grow. More sustainable solutions regarding housing, local food system planning and resiliency are on its way.

Not all ‘Gated’ Communities Have Gates

The term gated communities largely refers to communities or planned developments, secluded from the rest of the urban form, but in this article, the term gated communities will also encompass what I define as large luxury infill developments with private amenities, inaccessible to the majority of its neighborhood’s residents due to financial/income barriers and psychological symbolism that is meant to keep low income and most people of color excluded.

Front & York Luxury Development, DUMBO Brooklyn, NY with Private Amenities such as Swimming Pools, Gyms, and Terrace Parks.

Not all ‘Gated’ Communities Have Gates

Luxury mixed-use and residential developments are usually built with a variety of private amenities solely accessible to those who can afford the luxury cost of living. Today, we see new luxury residential and mixed use developments largely funded and built through real estate investment funds and equity firms in newly rezoned neighborhoods. Luxury apartment developers lure prospective tenants by flaunting opulent amenities. About every luxury apartment building website has a page featuring the apartment complex’s amenities. And for those who can afford it, the availability of certain privatized amenities such as gyms, pools, and parks can be a deal breaker in regions such as the New York, New Jersey metropolitan area, where space is at a premium.

The term gated communities largely refers to communities or planned developments, secluded from the rest of the urban form, but in this article, the term gated communities will also encompass what I define as large luxury infill developments with private amenities, inaccessible to the majority of its neighborhood’s residents due to financial/income barriers and psychological symbolism that is meant to keep low income and most people of color excluded. In addition, what may be deemed an amenity for the wealthy, can be essentials for people with lower incomes.

Historically, American housing policy and practice has shown that de facto racial segregation has found ways to separate where people live, by race, using pseudo mathematical equations meant to protect the commodification of housing. Is today’s separation of privatized amenities society’s way of segregating white and wealthy from poor people of color? Is it a modern method to advance segregation practices hidden through neo-liberalism?

The information in this article is no way meant to disparage residents of luxury developments as it is understandable that some people would like to pay a premium for privacy and good quality. However, this piece shall serve as a concession to acknowledge luxury amenities to tenant relationships and their overall impacts to society. So let’s explore the social, psychological and physical impacts these new developments may have on people in their surrounding communities. Diverse solutions, in which some are offered in the recommendations section, should help localities provide more housing options for different income-earners and provide greater public-private partnerships for community-based services.

“Not all gated communities have physical gates, some have monetary barriers, racist symbolism, and exclusionary psychological barriers that warrant low income and some people of color are not welcomed.”

Today's Residential Amenities were Yesterday's Neighborhood Essentials.

A few of today's private amenities were once public necessities or essentials by early urban planners and real estate developers. There are many examples that show early 20th century developers’ use to provide amenities inclusively for the community’s consumption.

Clarence Perry and the Neighborhood Unit

In the 1920s, Clarence Perry, developed the concept of the neighborhood unit, which was referred to as the ‘5-minute walk’. This concept included designated space for public community centers,and shared recreation and park spaces. Some of these concepts were built by Clarence Stein in Sunnyside, NY (Queens) and Rayburn, NJ.

The Neighborhood Unit

by Clarence Perry

Public Swimming Pools - New York City

The infamous Robert Moses built community parks and pools, in fact, in 1936, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) opened 11 pools in underserved communities. Each unveiling featured parades, water carnivals, blessings of the waters, swimming races, diving competitions, appearances by Olympic stars, and performances by swimming clowns. Every one of the pool complexes really was something to celebrate. They were so impressive, the Landmarks Preservation Commission places all 11 pools “among the most remarkable facilities ever constructed in the country.” Designed to accommodate 49,000 people across the city, each pool was larger than several Olympic-sized pools combined, and all were technologically extraordinary.

The massive pools featured under-water lighting, floodlighting, and a host of promenade lighting for night swimming. They each had heating systems, and innovations that set new standards in pool construction, such as “scum gutters'' that allowed sunlight to naturally kill bacteria, and foot baths that kept all swimmers in squeaky-clean repair

The pools were not officially segregated, but Robert Caro alleges in his biography of Moses that the Commissioner tried to discourage black New Yorkers from using pools in white neighborhoods by manipulating the temperature of the water.

Case Study: Jersey City’s “The Beacon”

Jersey City’s “The Beacon” is a vivid example of a literal gated community, with privatized amenities. Formerly, Jersey City Hospital, Jersey City Medical Center, the Beacon was redeveloped into a luxury apartment complex with various mixes of use, and opened for new tenants in 2016. Instead of integrating the existing street grid with the surrounding community of McGinley Square and Bergen Hill, the complex is cut off from public pedestrians, micromobile uses, transit, and vehicles by a fence that surrounds the entire 14 acre site, as shown below. Vehicular access is limited by a security guard and gate. The complex is hailed as the largest residential restoration project in the United States, in which 10 Art Deco buildings are federally landmarked. The developers pride itself as an “amenity rich apartment community… resort living… with [an] endless amount of modern conveniences and luxuries”. Some of these private amenities includes:

“gated community”, (yes this was actually listed as an amenity”;

onsite deli/ convenience store

Daily food trucks,

Dry cleaning pickup/drop off

Frequent resident events and activities,

Complimentary shuttle service [to/fromGrove Street PATH station, in downtown JC]

Indoor Swimming Pool

Residential Lounges and Studies.Club Rooms/Theaters

Business Centers/Conference Rooms

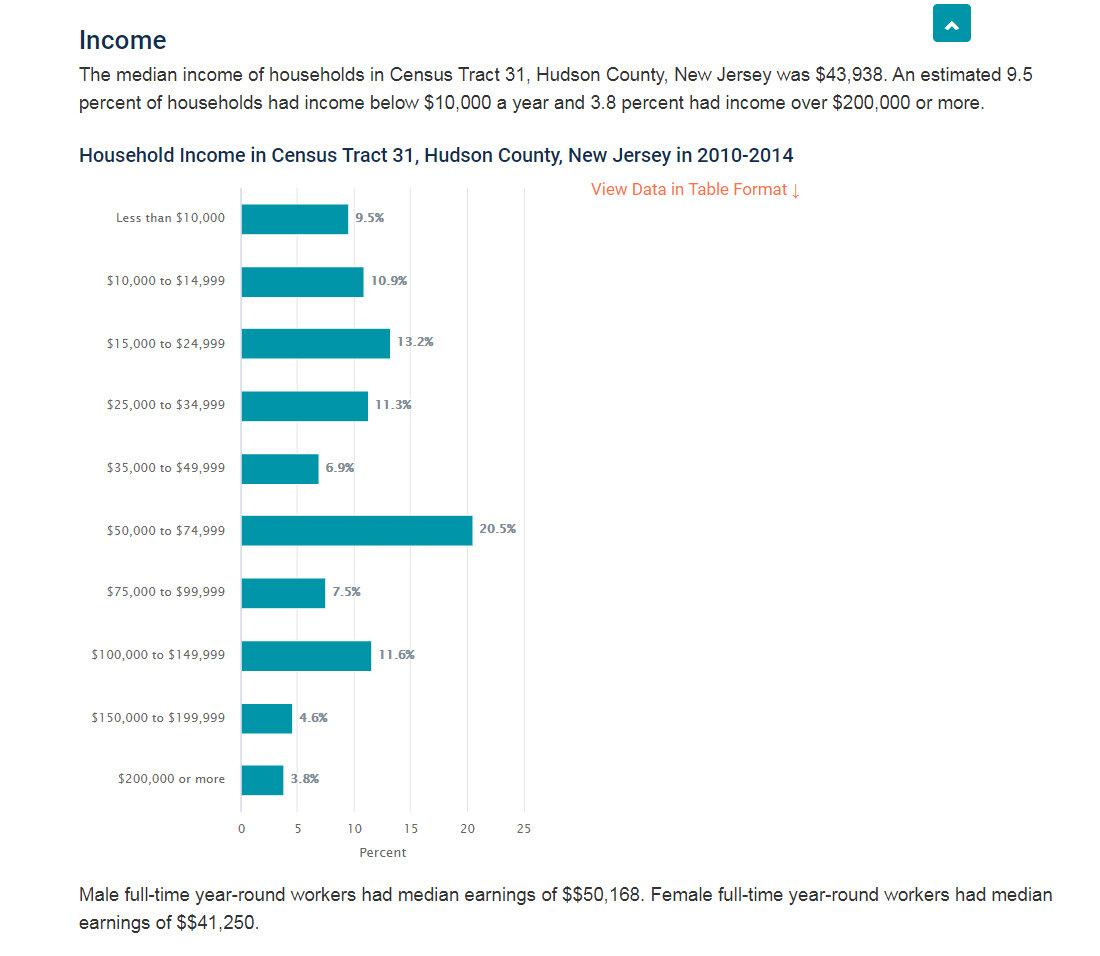

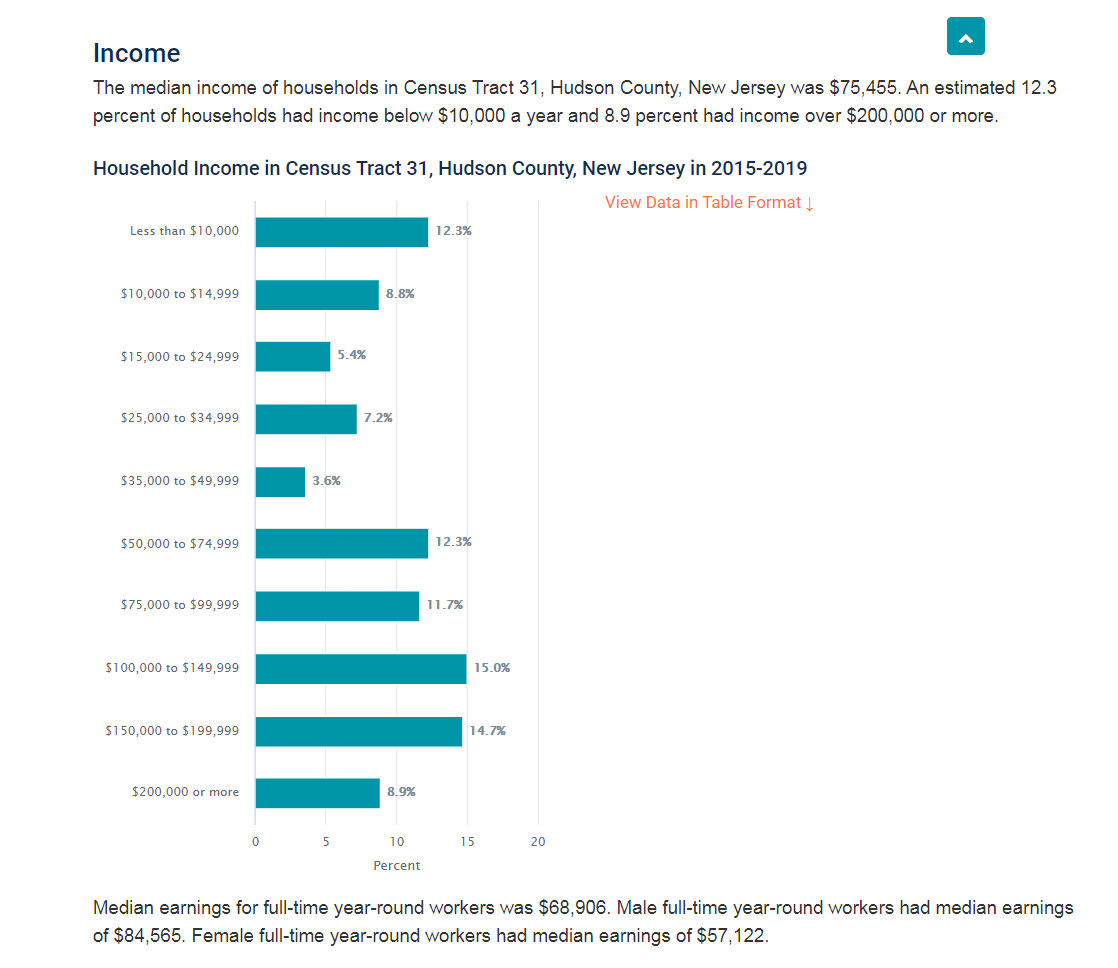

To enjoy these amenities, you have to be a resident, but the only caveat is you’d need a minimum of $1,480 for a 444 square feet studio, in which, for a census tract that is considered moderate to high risk for social vulnerability, most people cannot afford. The residents of the Beacon can literally live in their development and never interact with a person who was born and raised in the surrounding community. And on the other hand, a resident born and raised in the McGinley Sq and Bergen Hill neighborhoods, may never afford to be able to access the essentials and amenities exclusive to the Beacon residents, even if they wanted to pay for it separately from living there.

In addition, community residents surrounding the Beacon would have to travel a long distance to access public parks, public transportation, and a public pool. However, these essentials are gated, and only available to residents of the Beacon.

Other areas throughout the NYC region, including Williamsburg, are seeing luxury development with 'cruise-like' amenities as a culture killer, where artists and bohemians cannot afford or find the 'cool and artsy' places that once existed. Here are some other examples of luxury private developments with private amenities:

Front & York - Brooklyn NY

Solaris Lofts - Jersey City, NJ

The Ashland - Brooklyn, NY

Center Blvd at Hunter’s Point South - Long Island City, NY

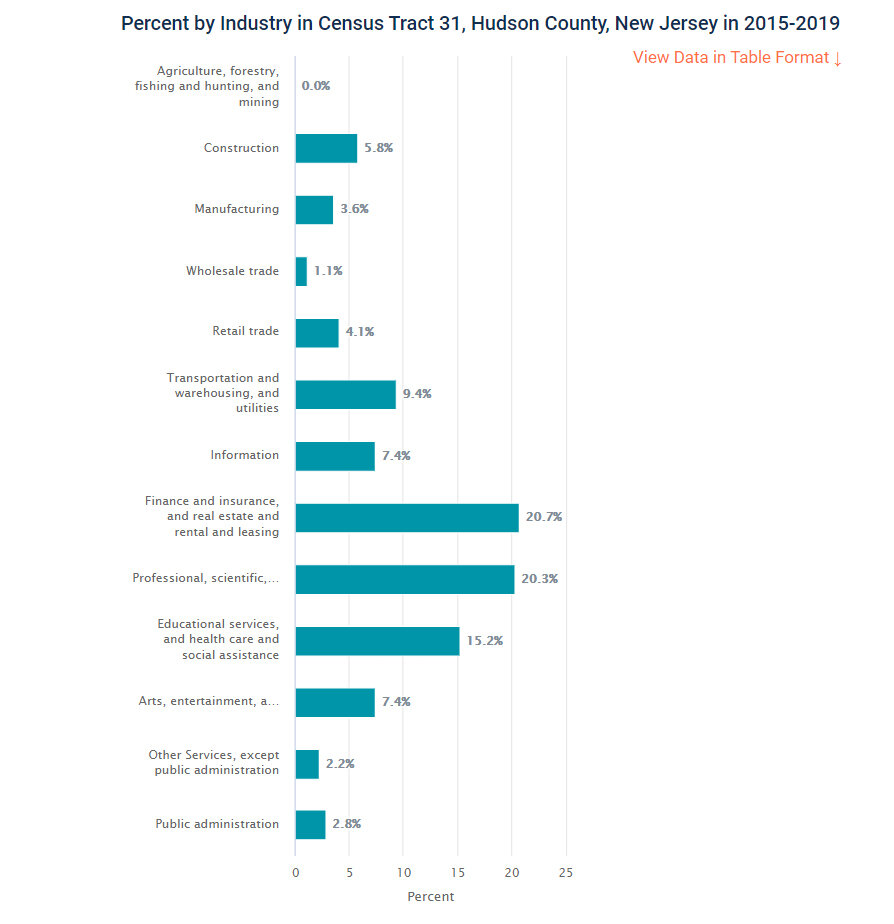

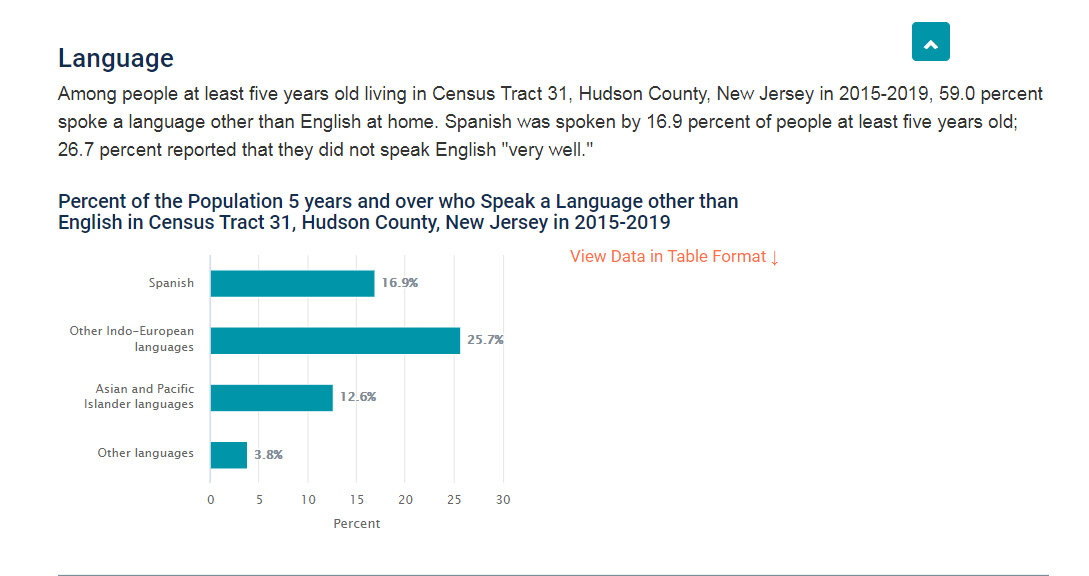

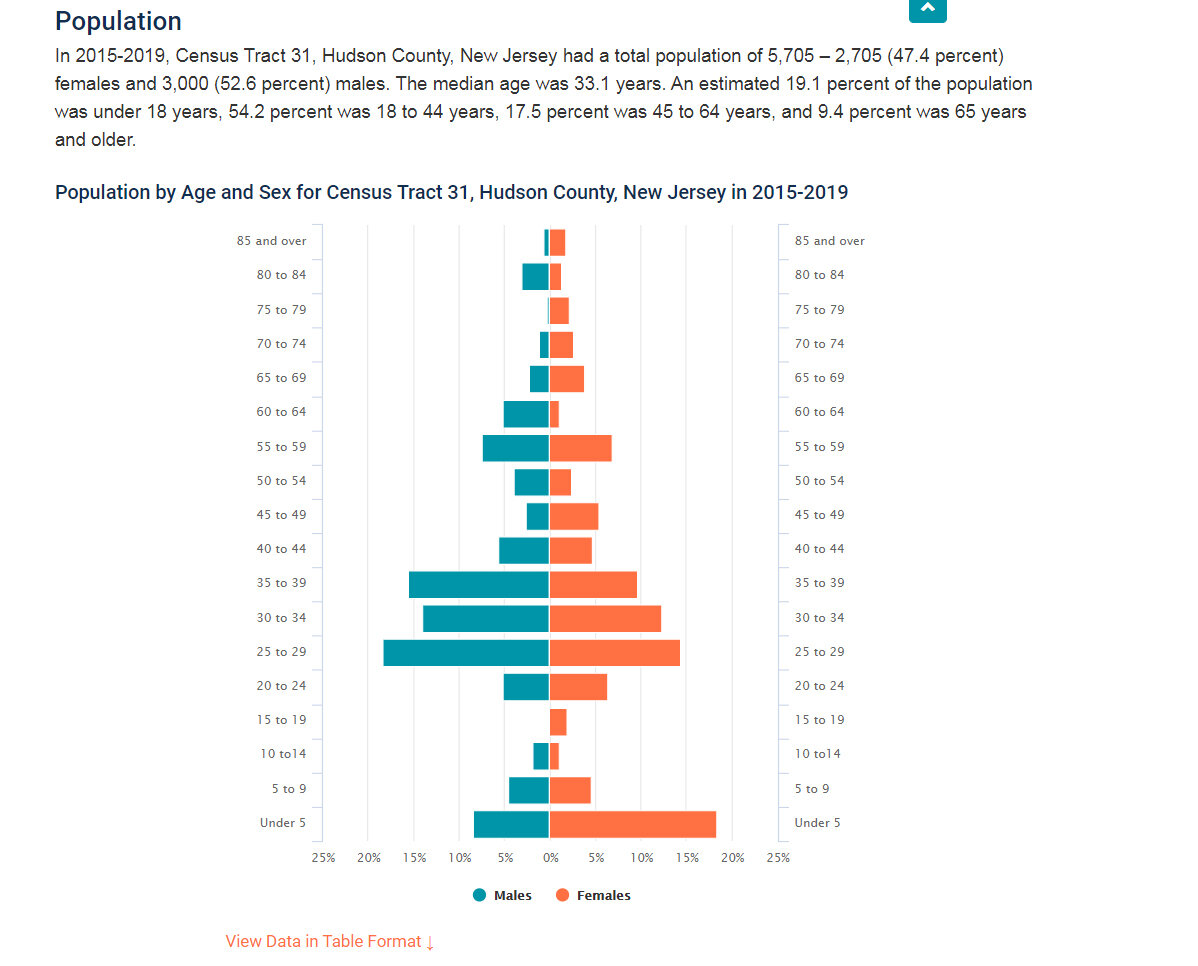

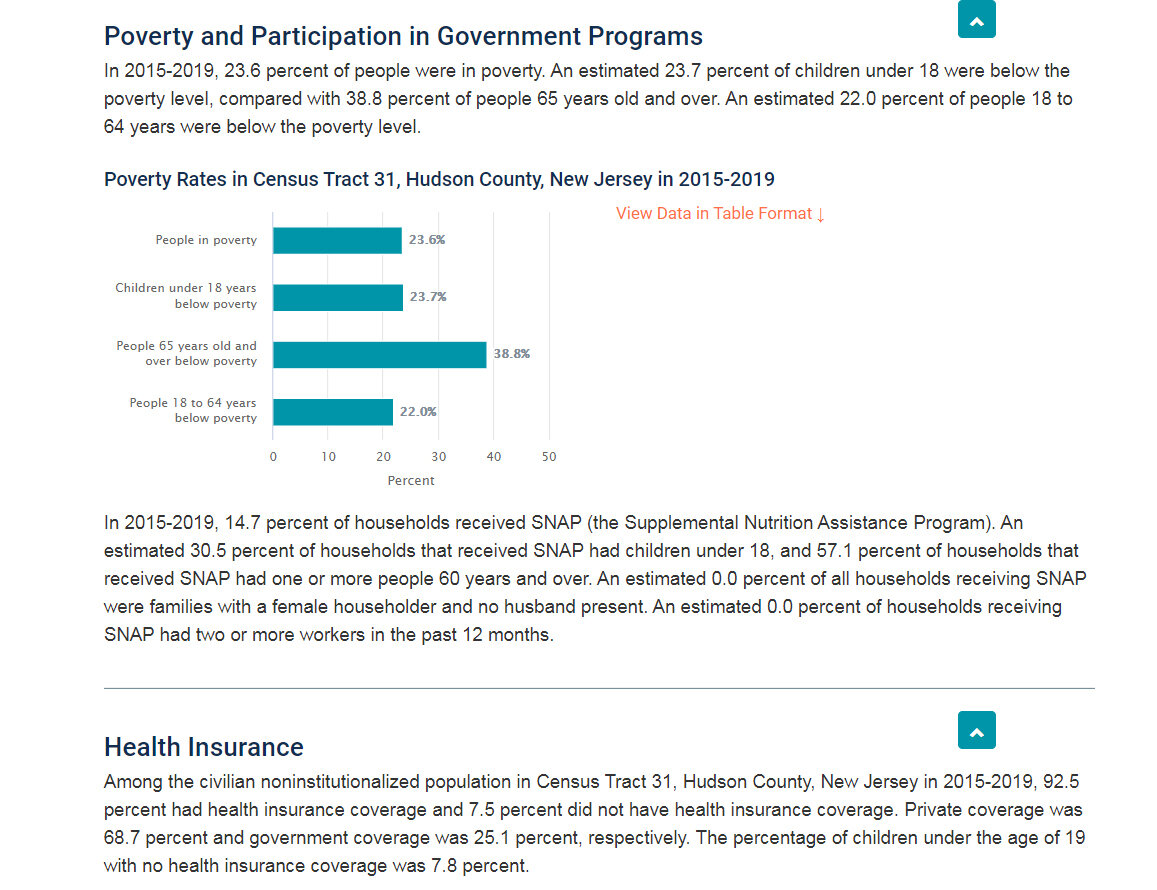

Bergen Hill, Jersey City Demographics

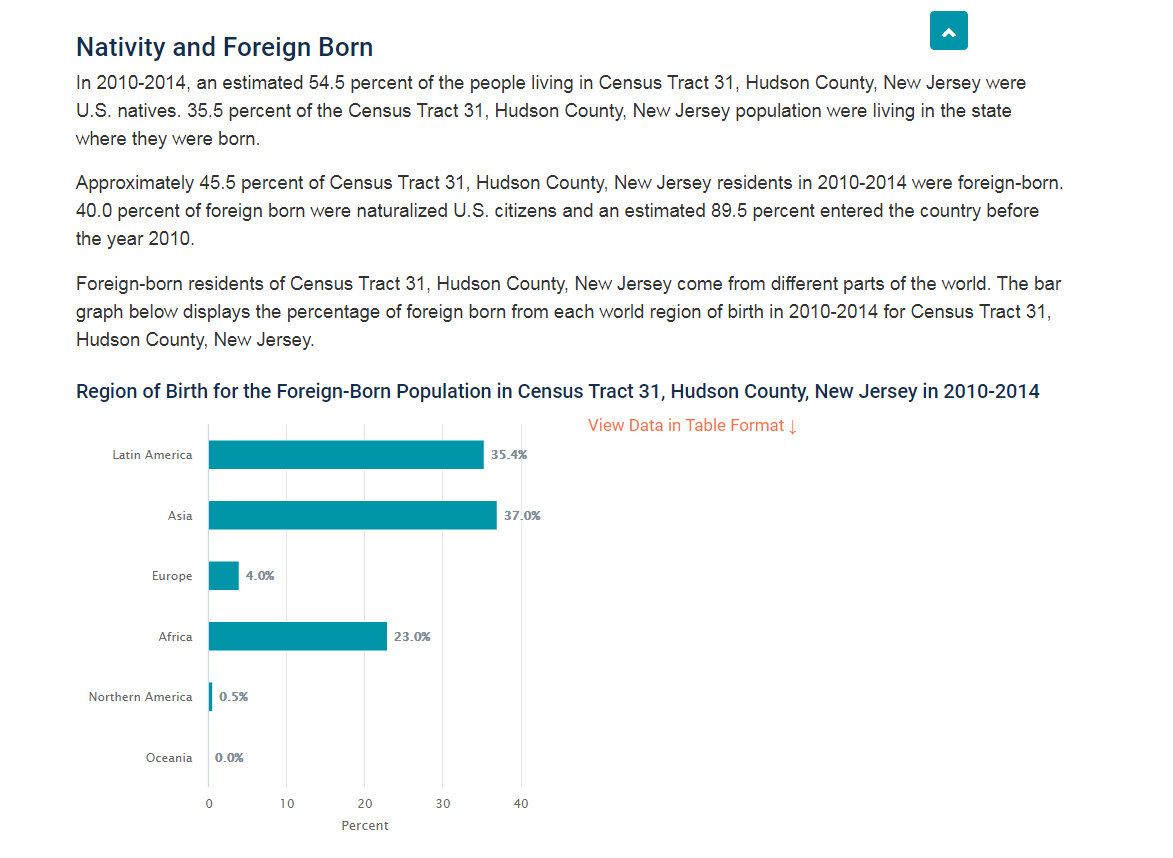

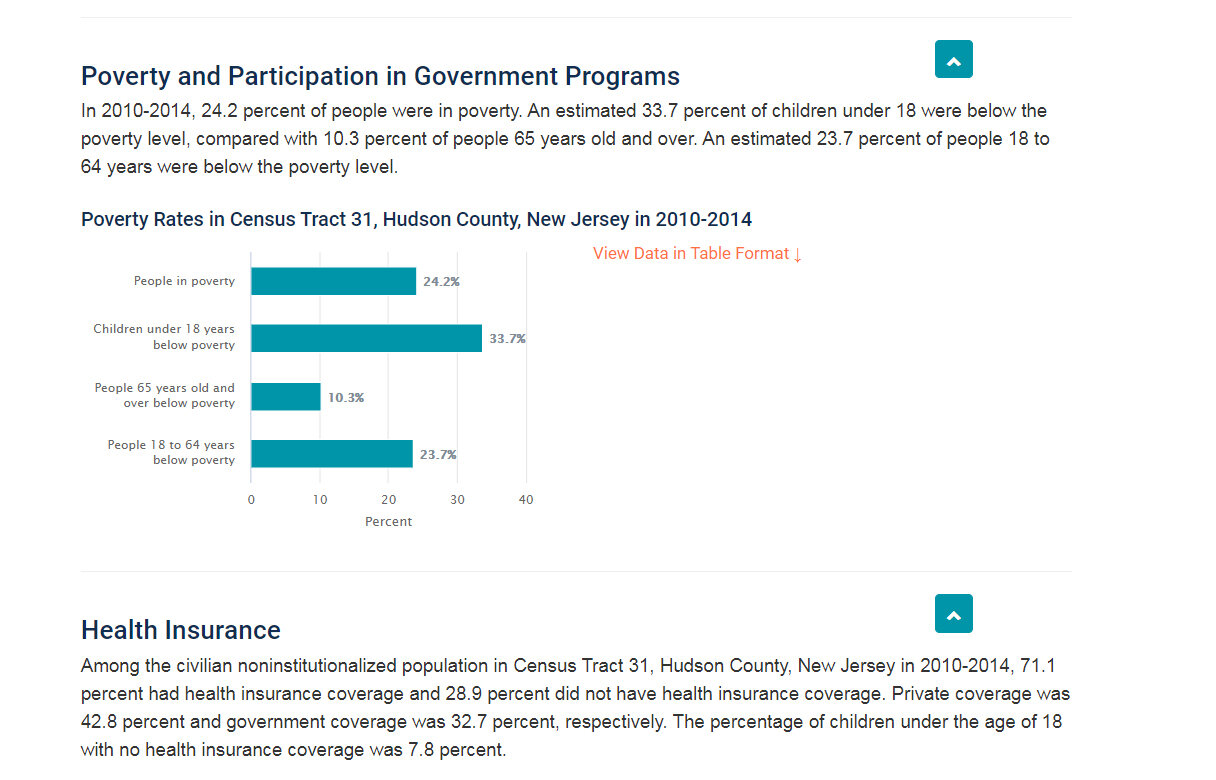

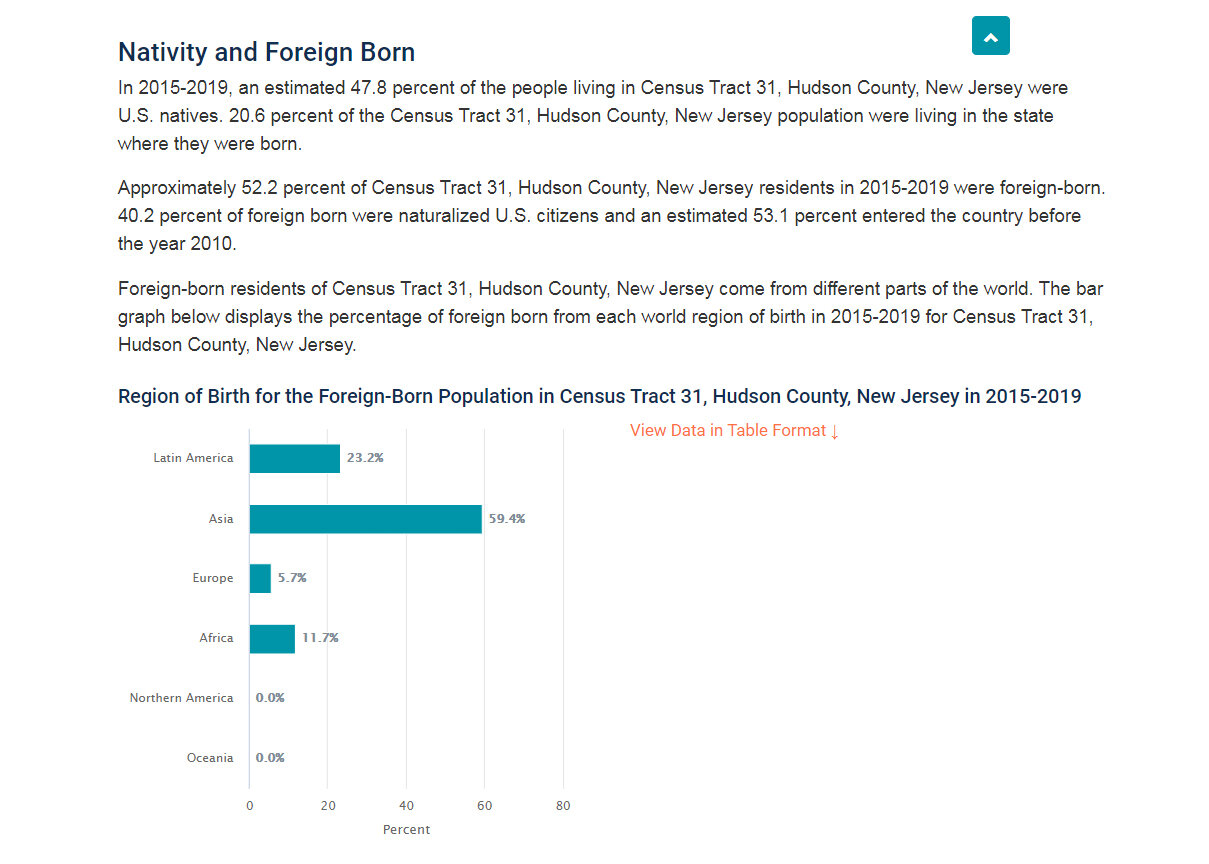

Approximately 52.2 percent of Census Tract 31, Hudson County, New Jersey residents in 2015-2019 were foreign-born. In 2015-2019, 23.6 percent of people were in poverty. An estimated 23.7 percent of children under 18 were below the poverty level, compared with 38.8 percent of people 65 years old and over. An estimated 22.0 percent of people 18 to 64 years were below the poverty level.

Below are a set of maps showing CDC’S social vulnerability index from years 2000 to 2016 for census tract 31, in which The Beacon is located. The data may be skewed as people with higher income has moved into the Beacon, private resources masked as amenities are not available to the greater community.

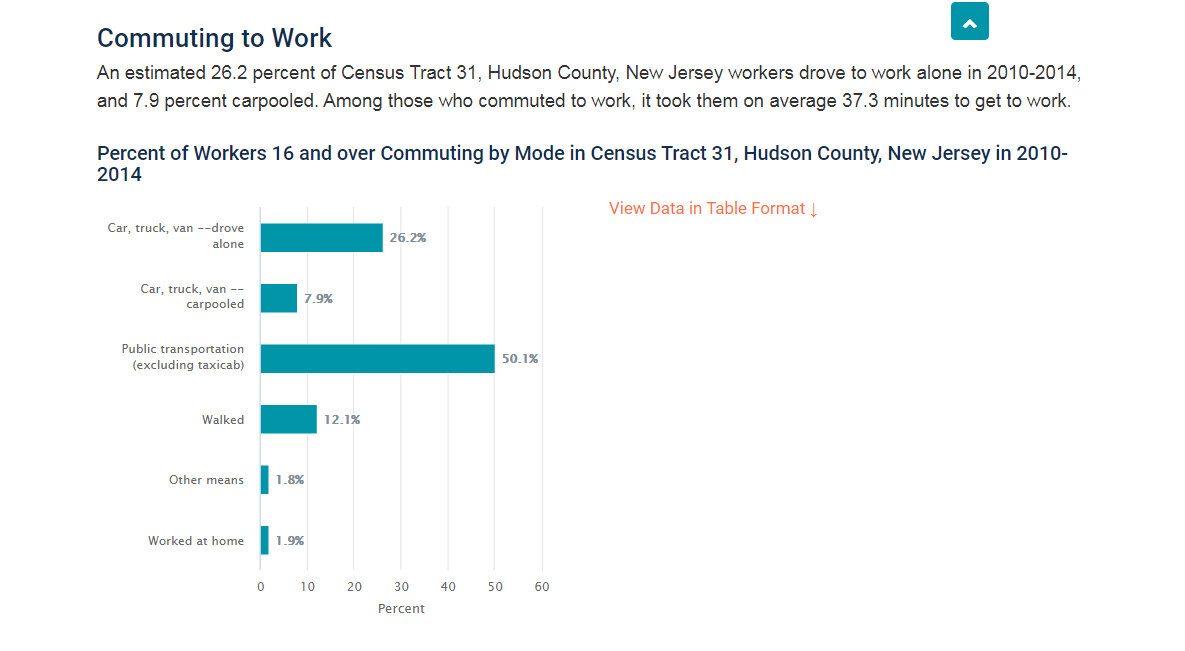

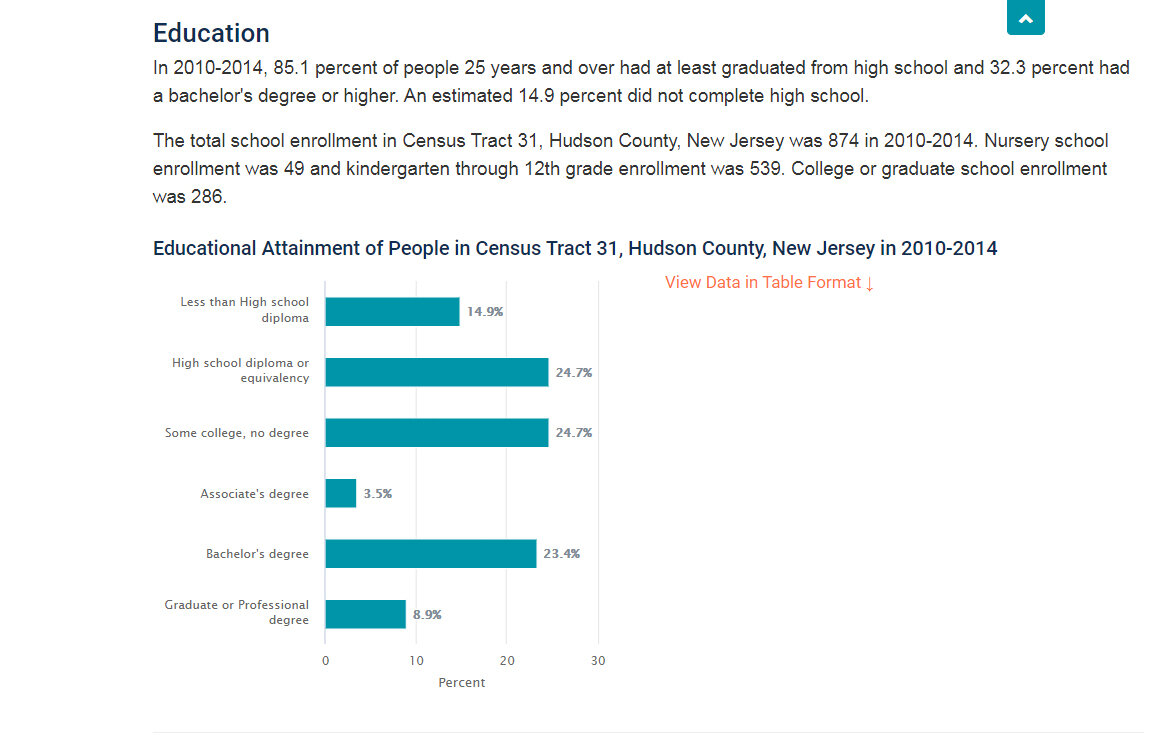

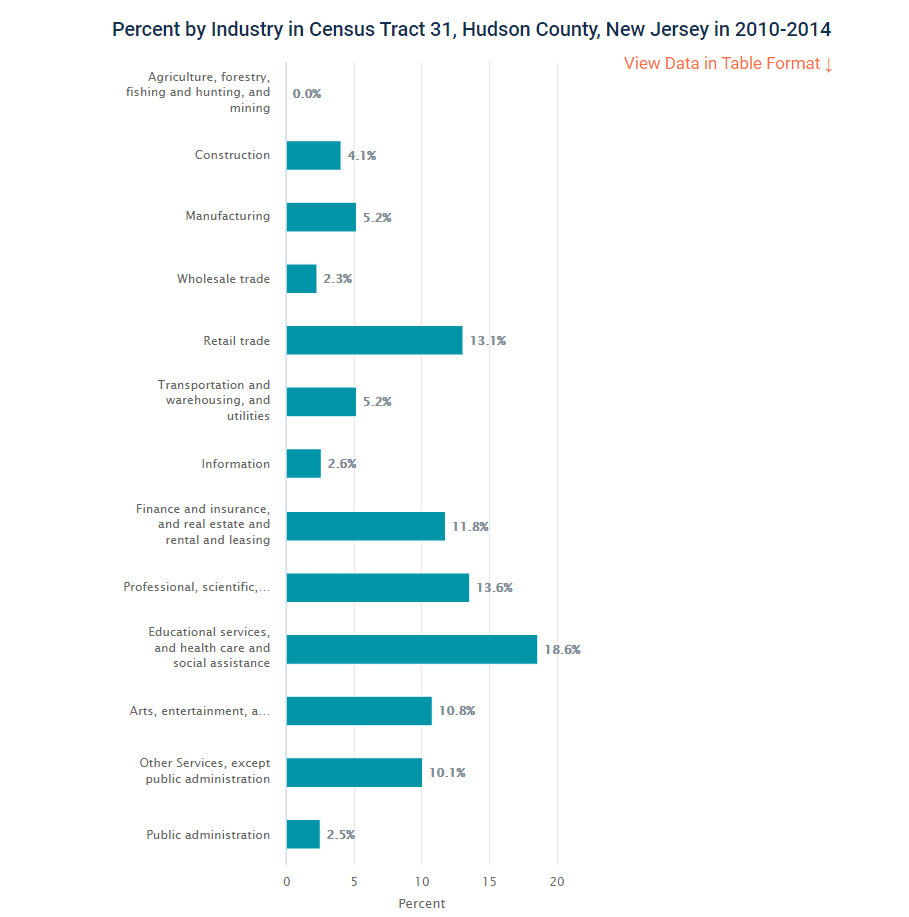

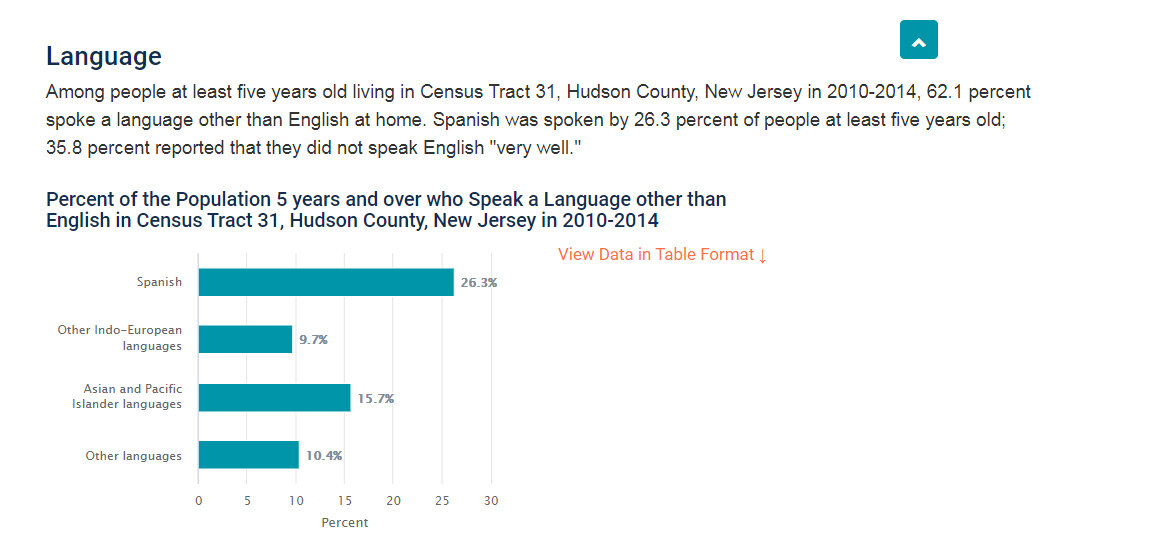

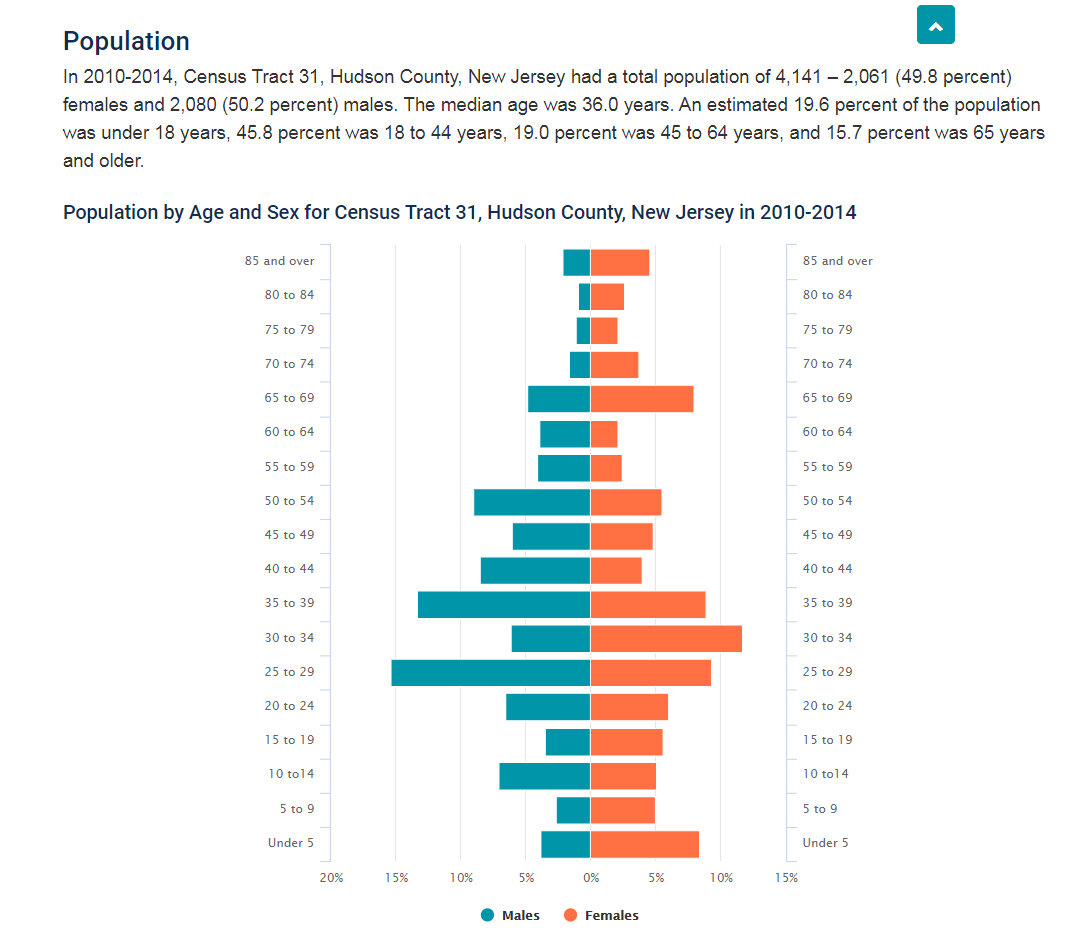

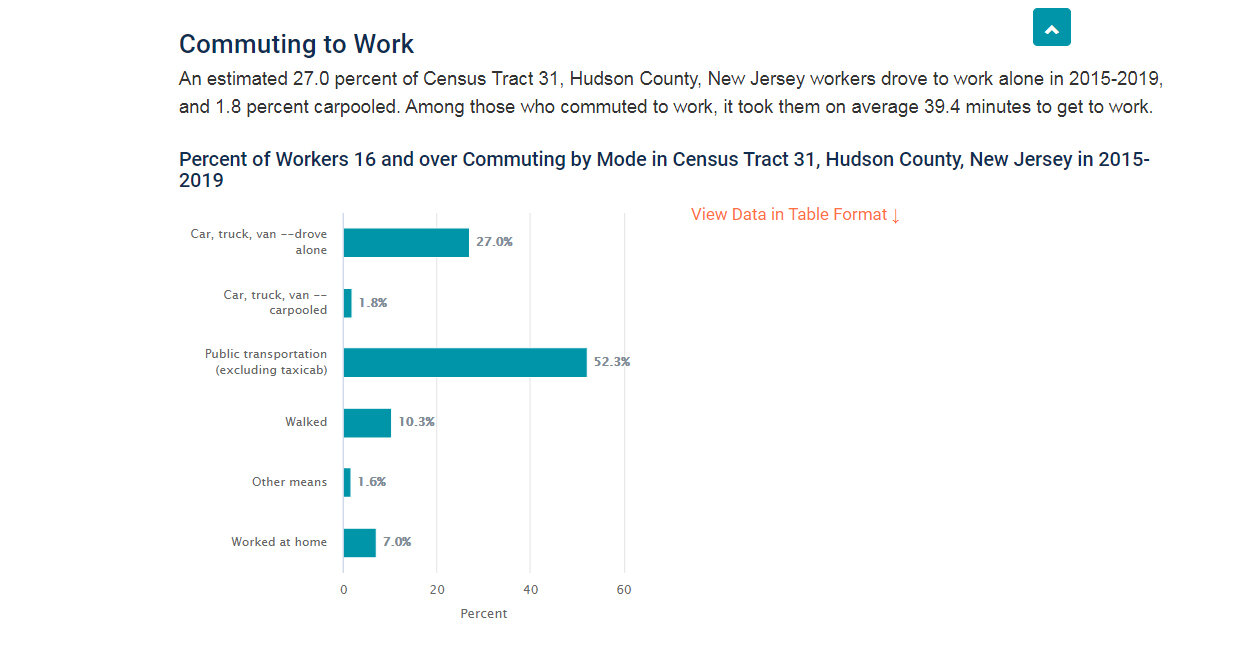

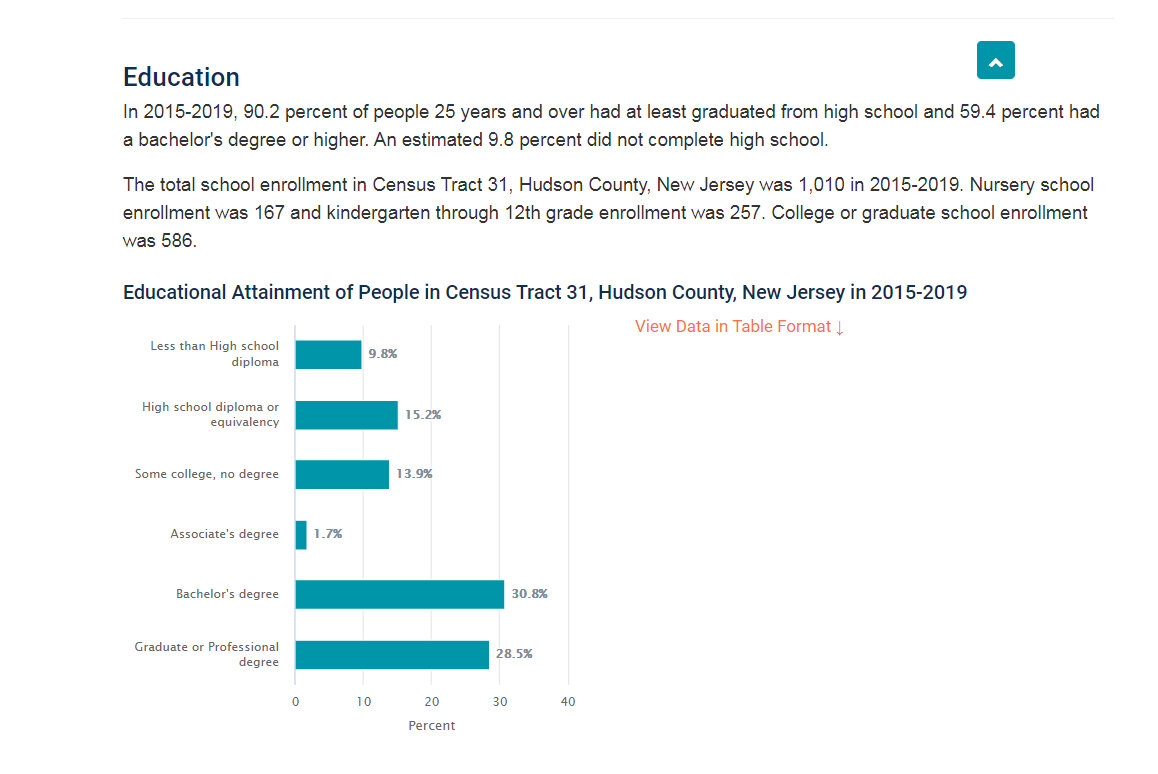

Scroll left or right to view Bergen Hill’s Demographic and Household Information for years 2010-2014.

The gallery afterwards shows the same characteristics but for the years 2015-2019. You will be able to compare each neighborhood demographic or characteristic to see how they have changed over the years.

Scroll left or right to view Bergen Hill’s Demographic and Household Information for years 2015-2019

The Environmental Psychology Behind ‘Gated Communities’

Below are excerpts from Gated Communities, Social Sustainability in Contemporary and Historic Gated Developments edited by Samer Bagaeen and Ola Uduku elaborating on the social, cultural and psychological impacts of gated communities throughout our society.

“Literature is available on whether gated community's play more into residents' idea for social status, as a members only club for fortified enclaves versus the discourse of fear, perceived as a bastion to keep the barbarians from the gate.”

“Residents in gated communities, especially in the U.S, are often bound by legal conditions that control lifestyle and social conditions within the community. These communities provide an example of how much a wider rise in contractual governance resulting from the new relation between the state, market and civil society designed to address concerns about social order.”

“The process of the accumulation of wealth, and structural advantage, economic and social, inherent in the gated community, mirrors the historic process by which the developed nations acquired their dominance and affluence. Colonization was a process of segregation and separation by which the rest of the world was reconstructed to provide the natural resources and captive markets for the metropolitan centre's and their elite. Gated communities are the neo-imperalist colonization of society: they are elite empires within a city that maintain the relationship of colonizers and the colonized, albeit in an urban setting. In this neo-colonial process. It is both the city as a central place and society as an inclusive unit that is being de/reconstructed.”

“Gated communities are a shining example of how not to provide security to a community, but to enhance and spread total insecurity by generating dysfunctional relationships. Societies marked by increasing equity has less to fear from internal social tensions. True physical and social security is provided by empowering the poor and the marginalized and opening the gates of gated communities. Valuing society and equitable social provisions can liberate the private space for families.”

Not all gated communities have physical gates. Some have monetary barriers, racist symbolism, and exclusionary psychological barriers that warrant low income and some people of color are not welcomed. The privatization of luxury housing amenities in low Income neighborhoods is the neo-colonial form of exclusionary racial zoning practices.

Modern luxury mixed use developments with exclusive privatized amenities located in low income black and brown communities is a form of de facto or “ society says its okay” form of racial segregation. Based on observation, the demographics of luxury apartment buildings in gentrified areas are almost the same: predominately white and affluent tenants surrounded by lower income people of color. There then appears to be a point of saturation where a certain amount of low-income and people of color populations are displaced, luring more developers to induce the effects of gentrification, in what I call an investor’s ‘Goldie Locks Neighborhood’.

“Investor’s ‘Goldie Locks Neighborhoods’ tend to be newly rezoned communities, in economically depressed, usually ethnic spaces deemed suitable for redevelopment and revitalization, often displacing the current residents.”

Income as a Tricky Exclusionary Practice in American Real Estate History

The Color of Law, by Richard Rothstein explains that the dated Federal Housing Administration (FHA)’s underwriting manual gave higher ratings to mortgage applications if there were no African-Americans living in or nearby the neighborhood, but also lowered the mortgage application risk estimates for individual properties with restrictive deed language. Restrictive deeds were recommended by the FHA because the federal agency thought exclusionary zoning ordinances were good enough to prevent low-income African-Americans from purchasing single family homes but inadequate in preventing middle income African-Americans from overcoming the financial barrier to afford the home. Thus, restrictive covenants explicitly prohibited resale to all African Americans, despite if they met the income criteria.

Income is still used as a financial barrier as an exclusionary tool to mixed-use gated communities, as shown by the Beacon luxury apartment example. By simply publicizing some amenities, the Beacon would offer essential community services to the surrounding community. The cost of luxury housing developments can be as high as 3x the cost of existing rent in a neighborhood, preventing most existing residents financial access to the amenities and in some cases the essentials of what only the wealthy can afford.

Many would argue that the Area Median Income (AMI) Index considers the median income of a broad area which includes higher income earners and is not a good indicator to determine who has a low enough income to win a lottery for an affordable housing unit in a luxury development. Some affordable housing lotteries in New York City, for example, have an interview process between the prospective affordable housing unit tenant and the property manager. Meanwhile, market-rate tenants are not required to interview for their prospective apartments.

There are other contemporary ‘restrictive covenant-like’ symbolisms and techniques disguised in plain sight that implies exclusionary housing to deter low-income earners and people of color.

Apartment Building Renderings Can Tell Us who is Really Welcomed

In some cases, luxury apartments seeking municipal approval provide renderings to local planning boards. The architect’s renderings include the proposed project in its completed stage and sometimes have illustrations of people for scale and to provide a visual context of the building.

This project seeking local planning board approval in the City of Orange, NJ a predominantly Black and Latino community. However, The architect has decided to only use white people to depict residents in the community. Does this imply that only white people are expected to reside in the building, or perhaps it's a hint for displacement of current black and brown residents. Whether the above is not true, the erasure of Black and brown people from spaces in America is nothing new, and has adverse implications to our society, with the main implication to people of color: you are not welcome here.

City of Orange, NJ Planning Department

The Concierge is the New Eye on the Streets

Jane Jacobs was hailed for explaining the importance of “eyes on the streets” mainly for security reasons and to deter crime. Jacobs argued that neighborhoods with street level porches and stoops were ideal for residents to keep an ‘eye on suspicious activity. However, as buildings are being built at greater densities and higher in height, residents turn to technology for eye on the streets, or in some cases, a concierge who not only takes care of essential hospitality and customer services, but may also act as the new “eye on the street’, guarding who may enter the building. In extreme cases, residents take their own policing into their own hands and question visitors who appear to be people of color before entering the premises.

Private Activities Harbor a New Type of Social Club Scene

Some property managers even go so far to keep their tenants happy by arranging tenant-only exclusive activities, such as game nights. The social impact of privatizing social activities and removing them from public spaces must be profound including less interactions between race and class, and a stagnation of plurality. The streets are meant to be like a ballet, filled with activities such as block parties, baseball games, hop scotch, double dutch, and the like, but with many activities privatized locked behind doors, a new model for a jetsonian city seems to re-emerge, with two worlds, the haves in their luxury tower in the parks and the have nots, on the streets. Some neighborhoods in the process of gentrifying lack essentials such as parks and fitness centers, but are privatized by luxury developers exclusive to their residents.

Separate Entrances and Inequitable Building Materials - Market Rate vs. Affordable Housing Rates

In this example, Teaneck residents filed a lawsuit against Jared Kushner’s company: Kushner Real Estate Acquisitions (KRE), in which the company has allegedly proposed to segregate affordable units from the development’s market rate units. The residents’ lawsuit argues that Teaneck’s planning board “violated its own regulations by approving a layout and design in which the affordable housing units are separate and distinctly unequal and placed in the most remote portion of the property.” It was also alleged that “the affordable units will not only be segregated but will be of lesser quality and not provide the same amenities as the market rate units.”

Developers will Attempt to Privatize the Public Realm as a Way to Control Who is Welcomed

If not checked by municipal planning board powers, developers can have their way and even attempt to privatize waterfront space as private parks for their luxury buildings. LeFrak Development originally submitted plans to revitalize an unused section of their downtown Jersey City waterfront property as a park only accessible to their residential tenants blocking access to the park from the general public. The Jersey City Planning Board quickly voted no against the private park, and allowed the developer to resubmit plans to feature provisions for a public park. This past March, Jersey City passed the revised plans and placed a deed restriction on the vacant property as a condition of approval, allowing the developers to construct a park only if it is accessible and open to the general public. The park will also serve as an extension to the existing Hudson River Waterfront Walkway.

Jersey Digs

Sky-high Amenities

The renderings for this proposed development in Midtown, Manhattan shows elevated parks in the sky with "distinct vertically stacked blocks, which are then staggered and laterally shifted to create numerous cantilevering landscaped outdoor terraces". It is not mentioned whether the terrace will be public or private space), however, if they are private, then consideration should be given to publicize some terraces for more access to green space. If it is public, then signage should help guide the public to access the terrace. Brookfield Place in Downtown Manhattan provides signage for the public to easily maneuver the office complex to access the Winter Gardens and the Hudson River Promenade.

Hostile Architecture in Public Spaces Managed by Private Entities

Some developers may incorporate public spaces as an agreement with their locality for density and height bonuses. As this New York Times article points out, developers may utilize hostile architectural designs such as, metal bars dividing a public bench, no loitering signs and actual fence and unlocked gates to deter people from accessing these public spaces. The article also mentions that security guards and doormen sometimes serve as gatekeepers by deterring the public from accessing privately managed public spaces. Hostile architectural design may lead to the underutilization of spaces and prove to have adverse psychological impacts to people experiencing homelessness.

A Few Recommendations on how to Mitigate the Adverse Impacts of Racial and Class Segregation from Luxury Developments

Implement universal design and inclusion practices. Localities should consider developers provide some publicized amenities in lieu of providing affordable housing units.

Allow residential amenities to be accessible by members of the public, at least, members of the community. There is precedent for this with commercial real estate through zoning regulations where developers are given height or density bonuses to build higher, in return for providing public spaces that benefit everyone.

Reform Area Median Income Index to be more local and less regional. Consider the neighborhood’s median income, not the statistical metropolitan area, which tends to have higher income.

Redevelopment plans, masters plans and neighborhood design guidelines should emphasize integrated streets and uses of public essentials and amenities and do away with privatization of streets and public spaces.

Consider recommendations from Chicago Department of Housing’s Racial Equity Impact Assessment Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP) - specifically the recommendation below:

Coordinate housing with other neighborhood amenities: The QAP should ensure residents have choices about where they can live affordably by ensuring that affordable developments are built in highly resourced, amenity-rich areas. One way to accomplish this is for the QAP to require applications to be coordinated with strategic initiatives like the City’s Equitable Transit Oriented Development (eTOD) Policy Plan to ensure alignment with core values for site selection and community benefit. The QAP should prioritize applications that incorporate the arts and local culture of a community.

Do you have any thoughts or additional recommendations? Please share your comments below or throughout our social media platforms.

Mutual Housing Associations: A Potential Solution To Slow Gentrification

It’s easy to assume that there is no way New York City can slow gentrification. The process of gentrification appears to have changed neighborhoods no one would have even imagined could become the expensive areas they are today. Numerous factors have contributed to the exponential rise in rents and property values: low taxes for developers, constant rezoning of low-income neighborhoods and manufacturing districts, and even tenant harassment serve as examples. In essence, most of these factors help either encourage speculation or are motivated by speculation. Rezoning of manufacturing districts to mixed-use districts shoot up property values, giving landlords of such buildings incentive to sell much higher than their purchase price, which will make for high rents of those mixed-use buildings. The potential of new, wealthier residents in a neighborhood may prompt a landlord to harass their low-income tenants to relocate in order to gain a larger profit from the building they own.

What are Mutual Housing Associations?

However, there are models that can be replicated in order to offset the process of gentrification. Mutual Housing Associations are a possible solution to slow gentrification where a restrictive sense of ownership is given to residents in order to prevent speculation and rising property values. Mutual Housing Associations are nonprofit corporations that provide affordable housing to community residents. Corporations usually develop housing with abandoned property, converted buildings like factories, or newly constructed houses. Whereas, MHAs are governed by a board of directors who are either residents of the buildings it owns or those who run the nonprofit also owns the MHA buildings. Residents become members of the MHA and may be given restrictive ownership of the property, with conditions that essentially prevent speculation. They may be able to sell their apartment, but for the same price they bought the unit, for example. MHAs operate and administer housing in different ways across the country, but in New York, there is one successful case of co-op conversion which can serve as a model to slow the process of gentrification.

“The model can still be replicated in neighborhoods like Far Rockaway and parts of South Queens, and parts of the Bronx where gentrification has not fully set in.”

Cooper Square Mutual Housing Association

One example of a successful MHA is the Cooper Square Mutual Housing Association (MHA). The Cooper Square MHA was founded by the Cooper Square Committee (CSC), who was re-tasked with redeveloping the Cooper Square Urban Renewal Area in the mid-1980s. The area, spanning six blocks in the Lower East Side, was to be demolished and replaced with low-income housing along with the relocation of residents by the request of the CSC in 1961. However, the CSC had a change of mind after the negative outcomes of such practices in other parts of the country a couple of decades later. The Revised Plan in 1986 called for the renovation of the to-be-demolished buildings within the six-block area, enlarging units and building full bathrooms for each unit.

The CSC also wanted to create “a multi-building cooperative in order to create an economy of scale to save money on fuel, insurance, supplies, and repairs. As permanently low-income housing, the apartments would be exempt from real estate taxes”. In order to finance the project, New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) both city and federal funds to renovate buildings, and donated them to the Cooper Square MHA, a nonprofit formed by the CSC in 1991 to manage the buildings . Over the course of the 1990s, the buildings designated for the MHA project underwent the City’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP). Eighteen buildings throughout the Lower East Side were approved, renovated, and sold to the MHA. Only one building, 89 East 3rd Street, took a more temporary approach. The building was entered into a Tenant Interim Lease (TIL) program with encouragement from the city, (Directory of NYC Housing Programs, NYU Furman Center).

The TIL program would convert the building to co-ops, meanwhile requiring rent restructuring and building management classes for its residents. When done, the tenants can buy their apartments for $250. However, in TIL buildings, tenants have the potential to be bought out prior to the full conversion which can slow down or even stop the process. They can also sell their units for a profit, which can kill the long-term goal of affordability. The building petitioned HPD to be allowed back into the program, with success. The tenants were relocated to other MHA buildings during renovations and sold by HPD to Cooper Square in 2008 .

By the 2010s, the MHA was finally ready to give its residents the opportunity to purchase their units. In 2012, the Cooper Square MHA “has scheduled about 280 co-op closings in 21 buildings during the first two weeks of December, comprising more than 80 percent of the association’s 327 apartments” (Anderson). Tenants purchased their apartments for $250, and can’t sell their apartments for significant profit. They can be sold for $250 to insider purchasers, and $1,800 for outside purchasers. They must sell the unit to the MHA first before it is transferred to the purchaser. The MHA rents out 24 ground-floor commercial spaces, which is an important source of funds (about 27%). The commercial tenants still pay a significantly reduced rent.

Strength, Weakness, Opportunity and Threat for MHAs in New York City

Overall, the history of the Cooper Square MHA explains a successful approach to non-speculative housing through the regulation of their units post co-op conversion. While this is an amazing method to preserve affordable housing, one must consider the state of New York in 2020 compared to the 20th century. The abandoned housing stock the CSC was able to acquire isn’t really there anymore, especially in a place like lower Manhattan. Luxury developments are usually the newly constructed housing, which is way more profitable to build than transferring ownership to MHAs. Barren land is scarce, expensive, and the cost to build housing on said land is much higher than decades before. New York City’s government, who was the City’s largest landlord in the 1970s and 1980s, sold many of its properties to spur development in the 1990s and 2000s. Regardless, the model can still be replicated in neighborhoods like Far Rockaway and parts of South Queens, and parts of the Bronx where gentrification has not fully set in. This may require a collaborative effort with the city and foundations willing to fund such non-speculative projects.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York and now residing in Far Rockaway, Queens, Sola Olosunde is a graduate student studying Urban Planning at Hunter College and is the winner of the Spring, 2020 Black + Urban's Sharing Solutions to Improve Our Spaces Initiative's Pilot Writing Contest. Sola is also a photographer and conducts historical research on New York City neighborhoods.